WHAT WE MEAN BY "GOSPEL KANJI"

Gospel Kanji explores a focused question:

whether the gospel message and the historical events concerning Jesus Christ may be reflected in the structure of certain Chinese characters—and, if so, whether event-specific gospel structures could have been embedded by early witnesses such as the Magi, who traveled from the East to worship Him.

“Gospel Kanji” is a working label for a focused line of inquiry.

When we examine words that are central to the biblical narrative—particularly those associated with the Messiah, sacrifice, forgiveness, and salvation—we observe that some kanji are composed of parts whose established meanings appear to align with the actual biblical events those words represent.

The claim is not that kanji contain Scripture, nor that meaning can be freely imposed onto characters. Rather, the question being explored is this:

Could some kanji preserve structured correspondences that cohere with the biblical narrative—especially as it is understood after the death and resurrection of Jesus?

In this project, kanji are treated as historical artifacts—objects to be examined critically, not sources of revelation. Scripture remains the interpretive standard.

WHO MIGHT HAVE EMBEDDED THE GOSPEL INTO KANJI?

The hypothesis begins with a well-known but often narrowly framed biblical episode: the visit of the Magi in Matthew 2.

Traditionally, the Magi are remembered primarily as gift bearers—bringing gold, frankincense, and myrrh. Yet Matthew presents them first and foremost as specialists in reading signs who, upon recognizing an unprecedented phenomenon, traveled from the East to confirm whether what they had observed corresponded to historical reality—and, upon confirmation, bore public witness to the birth of a king.

Within the broader scriptural pattern, those who encounter God’s redemptive acts are not merely recipients, but bearers of good news—called to return and speak of what they have seen and heard (cf. Isaiah 60:6; Isaiah 52:7; Psalm 96:3).

This leads to a historically cautious proposal:

If the Magi traveled from a distant homeland to worship the Messiah, it is reasonable to ask whether they also returned as bearers of that news—not only of a birth, but of its meaning.

When the prominent people, places, and events of the Matthew 2 account are compared with certain kanji associated with the account of the Magi and the gospel message, recurring structural correspondences emerge that invite closer examination.

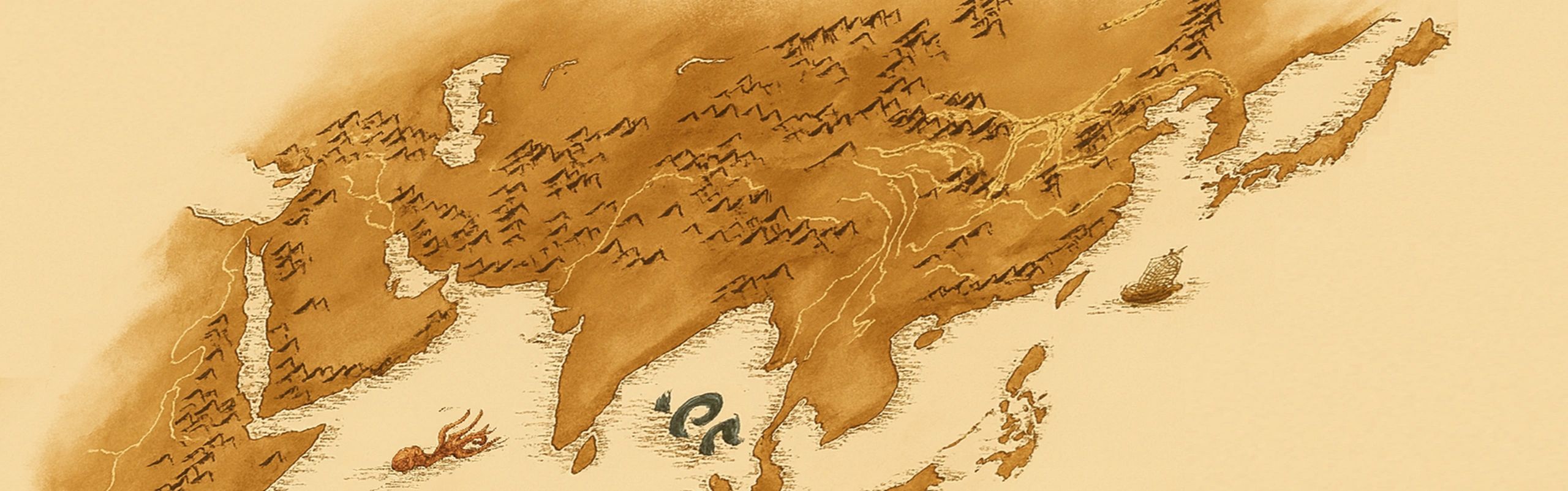

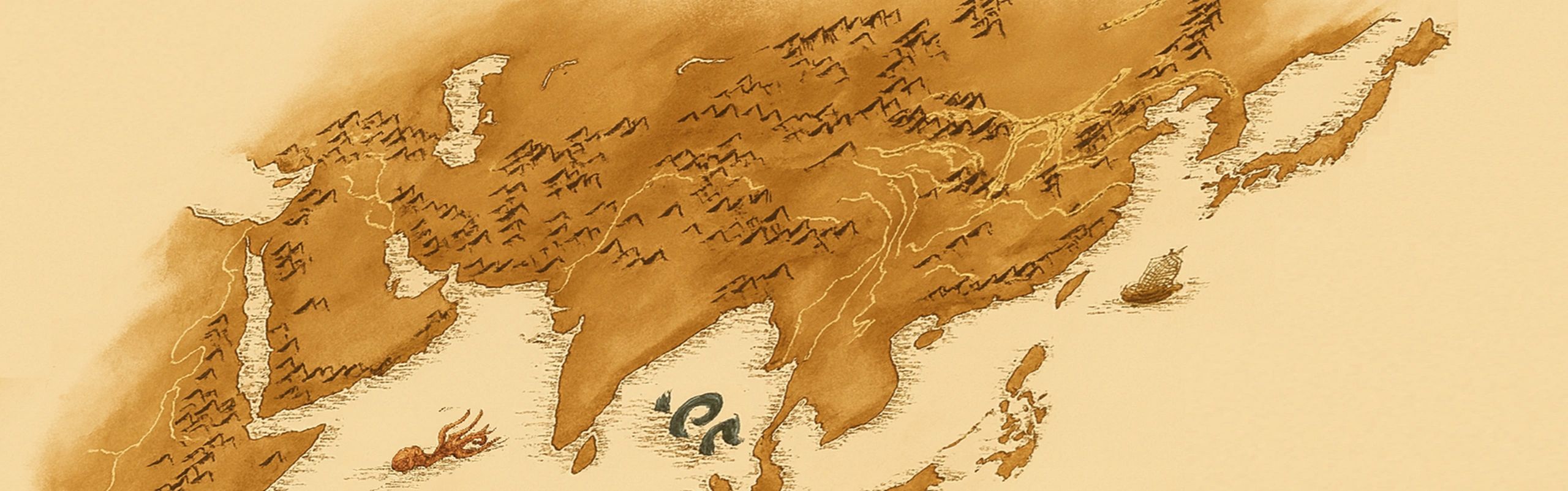

WHY LOOK TOWARD THE "ISLANDS OF THE RISING SUN"?

The Bible repeatedly frames God’s redemptive purpose as extending beyond Israel, toward the most distant nations.

Several strands come together here:

1. The “ends of the earth”

Isaiah records the Servant’s mission in explicitly global terms:

“I will make you a light for the nations,

that my salvation may reach to the ends of the earth.”

(Isaiah 49:6)

This language is later echoed directly in the New Testament:

“You will be my witnesses… to the ends of the earth.”

(Acts 1:8)

2. The “islands”

Isaiah repeatedly uses “the coastlands” or “islands” as a poetic designation for distant, often maritime peoples:

“He will not grow faint or be discouraged

till he has established justice in the earth;

and the coastlands wait for his law.”

(Isaiah 42:4)

“Listen to me, O islands,

and give attention, you peoples from afar.”

(Isaiah 49:1)

3. The “rising of the sun”

Malachi frames the worship of the true God as extending geographically from east to west:

“From the rising of the sun to its setting,

my name will be great among the nations.”

(Malachi 1:11)

Taken together, these texts do not identify a specific nation.

They do, however, establish a directional and theological horizon:

toward distant lands, toward the islands, toward the farthest reaches of the world—including, geographically speaking, the Far East.

Japan’s historical self-designation as the Land of the Rising Sun places it naturally within that horizon, making it a legitimate—though not exclusive—candidate for further investigation.

WHY PROPOSE TWO JOURNEYS BY THE MAGI?

Matthew records the Magi’s first journey:

their travel to Bethlehem to honor the birth of the Messiah.

That account, however, presents a limitation that must be addressed if the Gospel Kanji hypothesis is to be taken seriously.

Many of the kanji under examination reflect not only messianic expectation, but fully developed gospel events and claims—including the cross, judgment, resurrection, redemption, atonement, and kingship established through suffering. These are concepts that do not become clear within the biblical narrative until after the cross and resurrection.

This raises a historical and theological question:

How could characters reflect an understanding of events that had not yet occurred?

The proposal of a second journey exists to account for that level of detail.

The New Testament records a moment, roughly thirty years later, when Jerusalem is filled with people from across the known world:

“Parthians and Medes and Elamites…

visitors from Rome…

people from every nation under heaven.”

(Acts 2:9–11)

Pentecost marks the first public proclamation of the crucified and risen Christ, interpreted in light of Israel’s Scriptures.

If individuals from distant regions were present—as Acts explicitly states—then it is historically plausible that earlier witnesses to Jesus’ birth could have returned, not to see a coronation, but to encounter the meaning of His death and resurrection.

This proposal also aligns with Paul’s later reflection in Romans 10. Anticipating the objection that the gospel could not have reached so widely, Paul writes:

“But I ask, have they not heard?

Indeed they have, for

‘Their voice has gone out to all the earth,

and their words to the ends of the world.’”

(Romans 10:18)

Paul’s point is not that every individual had perfect knowledge, but that the proclamation of Christ had already spread remarkably far within the first century.

The second journey hypothesis is therefore not an attempt to add to Scripture, but to explain how post-resurrection theology—the cross, judgment, resurrection, and exalted kingship—could plausibly be reflected in written forms that appear to assume knowledge of those events.

Without a post-Pentecost encounter with the gospel, such detailed theological correspondence would be difficult to account for.

WHY THIS MATTERS

This project does not depend on proving the Magi’s origin or travel routes.

Even if:

- the Magi did not come from Japan

- the timeline remains speculative

- the historical trail is incomplete

The kanji themselves still function as effective teaching illustrations.

They can be used to:

- contrast messianic expectation with fulfillment

- explain biblical theology visually

- clarify gospel events across cultures

- tell the story of the Magi in a way that invites inquiry rather than demands agreement

Gospel Kanji does not seek to establish doctrine or replace Scripture.

It seeks to explore whether written language itself may preserve historical footprints of the gospel’s early global reach.

Contact Us

Better yet, see me in person!

If you have a radio show, podcast, event, or another audience, I would be thrilled to share these hidden stories that intertwine biblical narratives and Chinese characters, whether via Zoom or in person.

Gospel Kanji

Gospel Kanji

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.